Mapping Poverty as a Form of Transformative Research

There is a direct relationship between a city’s built environment and who benefits from it economically. Our phrasing even betrays this connect: “the bad part of town” or “the other side of the tracks.” Or to put it another way, cities naturally obscure parts of the city that are distressed or neglected. In some cities, commuter trains are conveniently underground in the worst patches of the city. Other cities use trees or highways to divert attention from disinvested communities. For example, Geary Boulevard in San Francisco created a barrier between government subsidized housing in Western Addition and the affluent Pacific Heights neighborhood. By visualizing poverty, we can gain insight into realities, causes, and potential solutions to poverty.

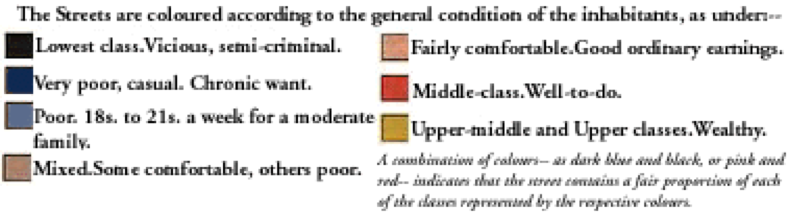

In the late nineteenth century, Charles Booth used mapping to visualize poverty in London. Laura Vaughan brings Booth’s important work to light in her recent book Mapping Society: The Spatial Dimensions of Social Cartography. Vaughan describes social cartography as mapping with the purpose of representing particular aspects of society at a given time and place.[1] Visualizing societal issues in terms of spatial organization can offer unique insights into those issues. Vaughan explains further:

It will demonstrate how a better understanding of the relationship between society and space can shed light on fundamental urban phenomena that normally tend to be seen purely as by-products of social structures. By bringing spatial analysis into the foreground, it emphasises the power of space in shaping society over time.[2]

Vaughan’s book offers detailed case after case of ways mapping was used to highlight emerging concerns in cities. She notes the work of Booth and others coincided with new technology that made mapping easier. Charles Booth led the way in harnessing technology for the sake of addressing urban challenges.

Today, technological advances have made mapping research even more accessible. However, one might be tempted to say that since we have Google maps we do not need to put in much effort. Navigational mapping is certainly helpful, but it is not the social cartography that Vaughan is highlighting. In recent years, new organizations have taken up this work of mapping poverty.

It was the industrial era that accelerated urbanization in Europe and North America. Cities were overwhelmed by the numbers of people seeking work in the factories and sweatshops of the cities. Tenements were pushed beyond their capacity for humane conditions. Many places in Asia and Africa have seen similar surges in urban growth. This growth has outpaced urban planning and infrastructure. In other words, for these burgeoning settlements to gain access to what the city can offer, real data is needed.

Two organizations are doing social cartography well. One is from the academy and the other is from the grassroots. The Mansueto Institute of Urban Innovation at the University of Chicago is working on an open access project called the Million Neighborhoods Map. Their goal is “to provide municipal leaders and community residents with a tool to help inform and prioritize infrastructure projects in underserviced neighborhoods, including informal urban settlements that are sometimes known as ‘slums.’”[3] This tool combines the latest technology with the University of Chicago urban research legacy for the sake of those who were not recognized by traditional government record.

From the grassroots, Slum Dwellers International (SDI) is best described as a network of local, community-based organizations who contribute research in order to advocate for under-resourced urban poor neighborhoods. Instead of the big data approach taken by the Mansueto Institute, SDI emphasizes getting people on the ground to compile data. Their mantra is “We don’t need others to collect information on our settlements. We can do it ourselves!” SDI equips people for research which becomes the basis for advocacy and activism for urban informal settlements.

Laura Vaughan’s research in historical social cartography gives us the language and categories to see the importance of mapping as a tool for urban flourishing:

Importantly, one of the most constant features of the historical maps presented in this book has been their demonstration of the importance of urban form and spatial configuration in shaping social outcomes: this is repeatedly substantiated by the fact that urban problems frequently persist over many years, even decades.[4]

A visualization of the spatial arrangement of poverty can reveal the impact of the built environment and infrastructure on the urban poor.

Figure 1 http://www.umich.edu/~risotto/maxzooms/ne/nej56.html (cropped). Original: Charles Booth’s Labour and Life of the People. Volume 1: East London (London: Macmillan, 1889). Public Domain

Figure 1 http://www.umich.edu/~risotto/maxzooms/ne/nej56.html (cropped). Original: Charles Booth’s Labour and Life of the People. Volume 1: East London (London: Macmillan, 1889). Public Domain

[1] Laura Vaughan, Mapping Society: The Spatial Dimensions of Social Cartography (London: UCL Press, n.d.), 1.

[3 ]Mansueto Institute for Urban Innovation, “Million Neighborhoods: Mapping Fast-Growing Informal Settlements in Africa,” The University of Chicago (blog), 2019, https://miurban.uchicago.edu/2019/11/14/millionneighborhoodsmap/.